Yoga: The Union of Subject and Object

Continuing our series on Sanatan Dharma by Swami Krishnananda

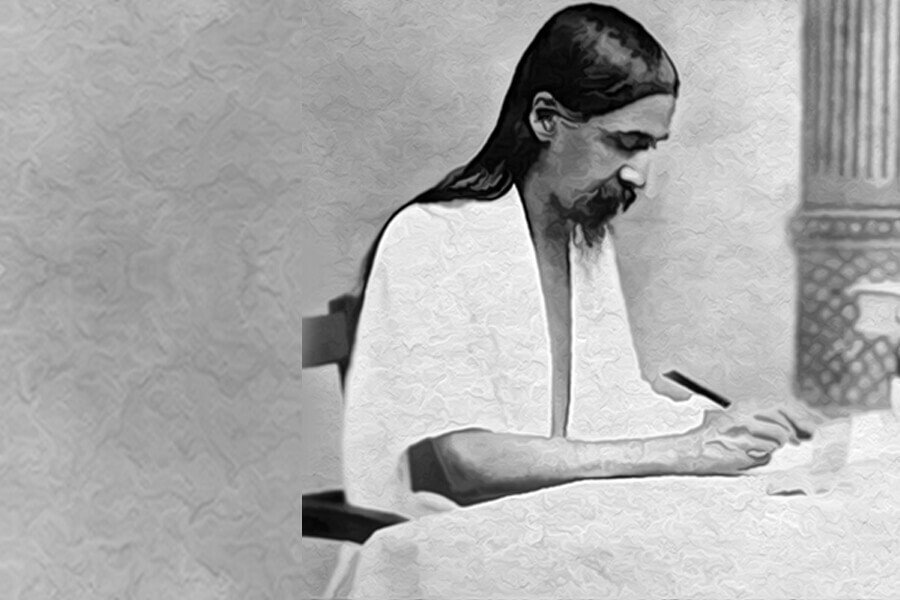

Sri Aurobindo wrote a letter to his younger brother, Barin Ghosh in 1920, explaining, among other things, his Yoga and spiritual approach.

First, about your yoga. You want to give me the charge of your yoga, and I am willing to accept it. But this means giving it to Him who, openly or secretly, is moving me and you by His divine power. And you should know that the inevitable result of this will be that you will have to follow the path of yoga which He has given me, the path I call the Integral Yoga. This is not exactly what we did in Alipur jail, or what you did during your imprisonment in the Andamans. What I started with, what Lele gave me, what I did in jail — all that was a searching for the path, a circling around looking here and there, touching, taking up, handling, testing this and that of all the old partial yogas, getting a more or less complete experience of one and then going off in pursuit of another. Afterwards, when I came to Pondicherry, this unsteady condition ceased. The indwelling Guru of the world indicated my path to me completely, its full theory, the ten limbs of the body of the yoga. These ten years he has been making me develop it in experience; it is not yet finished. It may take another two years. And so long as it is not finished, I probably will not be able to return to Bengal. Pondicherry is the appointed place for the fulfillment of my yoga—except indeed for one part of it, that is, the work. The centre of my work is Bengal, but I hope its circumference will be the whole of India and the whole world.

Later I will write to you what my path of yoga is. Or, if you come here, I will tell you. In these matters the spoken word is better than the written. For the present I can only say that its fundamental principle is to make a synthesis and unity of integral knowledge, integral works and integral devotion, and, raising this above the mental level to the supramental level of the Vijnana, to give it a complete perfection. The defect of the old yoga was that, knowing the mind and reason and knowing the Spirit, it remained satisfied with spiritual experience in the mind. But the mind can grasp only the fragmentary; it cannot completely seize the infinite, the undivided. The mind's way to seize it is through the trance of samadhi, the liberation of moksha, the extinction of nirvana, and so forth. It has no other way. Someone here or there may indeed obtain this featureless liberation, but what is the gain? The Spirit, the Self, the Divine is always there. What the Divine wants is for man to embody Him here, in the individual and in the collectivity—to realise God in life. The old system of yoga could not synthesise or unify the Spirit and life; it dismissed the world as an illusion or a transient play of God. The result has been a diminution of the power of life and the decline of India. The Gita says: utsīdeyur ime lokā na kuryām karma ced aham, "These peoples would crumble to pieces if I did not do actions." Verily "these peoples" of India have gone down to ruin. What kind of spiritual perfection is it if a few ascetics, renunciates, holy-men and realised beings attain liberation, if a few devotees dance in a frenzy of love, god-intoxication and bliss, and an entire race, devoid of life and intelligence, sinks to the depths of darkness and inertia?

First one must have all sorts of partial experience on the mental level, flooding the mind with spiritual delight and illuminating it with spiritual light; afterwards one climbs upwards. Unless one makes this upward climb, this climb to the supramental level, it is not possible to know the ultimate secret of world-existence; the riddle of the world is not solved. There, the cosmic Ignorance which consists of the duality of Self and world. Spirit and life, is abolished. Then one need no longer look on the world as an illusion: the world is an eternal play of God, the perpetual manifestation of the Self. Then is it possible fully to know and realise God—samagram mām jnāturh pravistum, "to know and enter into Me completely", as the Gita says. The physical body, life, mind and reason, Supermind, the Bliss-existence—these are the Spirit's five levels. The higher we climb, the nearer comes a state of highest perfection of man's spiritual evolution.

When we rise to the Supermind, it becomes easy to rise to the Bliss. The status of indivisible and infinite Bliss becomes firmly established — not only in the timeless Supreme Reality, but in the body, in the world, in life. Integral existence, integral consciousness, integral bliss blossom out and take form in life. This endeavour is the central clue of my yogic path, its fundamental idea. But it is not an easy thing. After fifteen years I am only now rising into the lowest of the three levels of the Supermind and trying to draw up into it all the lower activities. But when the process is complete, there is not the least doubt that God through me will give this supramental perfection to others with less difficulty. Then my real work will begin. I am not impatient for the fulfillment of my work. What is to happen will happen in God's appointed time. I am not disposed to run like a madman and plunge into the field of action on the strength of my little ego. Even if my work were not fulfilled, I would not be disturbed. This work is not mine, it is God's. I listen to no one else's call. When I am moved by God, I will move…

Next I will discuss some of the specific points raised in your letter. I do not want to say much here about what you write as regards your yoga. It will be more convenient to do so when we meet. But there is one thing you write, that you admit no physical connection with men, that you look upon the body as a corpse. And yet your mind wants to live the worldly life. Does this condition still persist? To look upon the body as a corpse is a sign of asceticism, the path of nirvana. The worldly life does not go along with this idea. There must be delight in everything, in the body as much as in the spirit. The body is made of consciousness, the body is a form of God. I see God in everything in the world. Sarvam idam brahma, vāsudevah sarvamiti ("All this here is the Brahman", "Vasudeva, the Divine, is all”) — this vision brings the universal delight. Concrete waves of this bliss flow even through the body. In this condition, filled with spiritual feeling, one can live the worldly life, get married or do anything else. In every activity one finds a blissful self- expression of the divine…

Next, in reference to the divine community, you write, “I am not a god, only some much-hammered and tempered steel." I have already spoken about the real meaning of the divine community. No one is a god, but each man has a god within him. To manifest him is the aim of the divine life. That everyone can do. I admit that certain individuals have greater or lesser capacities. I do not, however, accept as accurate your description of yourself. But whatever the capacity, if once God places his finger upon the man and his spirit awakes, greater or lesser and all the rest make little difference. The difficulties may be more, it may take more time, what is manifested may not be the same — but even this is not certain. The god within takes no account of all these difficulties and deficiencies; he forces his way out. Were there few defects in my mind and heart and life and body? Few difficulties? Did it not take time? Did God hammer at me sparingly — day after day, moment after moment? Whether I have become a god or something else I do not know. But I have become or am becoming something —whatever God desired. This is sufficient. And it is the same with everybody; not by our own strength but by God's strength is this yoga done…

…Let me tell you briefly one or two things I have been observing for a long time. It is my belief that the main cause of India's weakness is not subjection, nor poverty, nor a lack of spirituality or religion, but a diminution of the power of thought, the spread of ignorance in the "birthplace of knowledge”. Everywhere I see an inability or unwillingness to think — incapacity of thought or "thought-phobia".

This may have been all right in the mediaeval period, but now this attitude is the sign of a great decline. The mediaeval period was a night, the day of victory for the man of ignorance; in the modern world it is the time of victory for the man of knowledge. He who can delve into and learn the truth about the world by thinking more, searching more, labouring more, gains more power. Take a look at Europe. You will see two things: a wide limitless sea of thought and the play of a huge and rapid, yet disciplined force. The whole power of Europe is here. It is by virtue of this power that she has been able to swallow the world, like our tapaswis of old, whose might held even the gods of the universe in terror, suspense, subjection.

People say that Europe is rushing into the jaws of destruction. I do not think so. All these revolutions, all these upsettings are the first stages of a new creation. Now take a look at India. A few solitary giants aside, everywhere there is your simple man, that is, your average man, one who will not think, cannot think, has not an ounce of strength, just a momentary excitement. India wants the easy thought, the simple word; Europe wants the deep thought, the deep word. In Europe even ordinary labourers think, want to know everything. They are not satisfied to know things halfway, but want to delve deeply into them. The difference lies here. But there is a fatal limitation to the power and thought of Europe. When she enters the field of spirituality, her thought-power stops working. There Europe sees everything as a riddle, nebulous metaphysics, yogic hallucination — "It rubs its eyes as in smoke and can see nothing clearly?” But now in Europe not a little effort is being made to surmount even this limitation. Thanks to our forefathers, we have the spiritual sense, and whoever has this sense has within his reach such knowledge, such power, as with one breath could blow all the immense strength of Europe away like a blade of grass. But power is needed to get this power.

We, however, are not worshippers of power; we are worshippers of the easy way. But one cannot obtain power by the easy way. Our forefathers swam in a vast sea of thought and gained a vast knowledge; they established a vast civilisation. But as they went forward on their path they were overcome by exhaustion and weariness. The force of their thought decreased, and along with it decreased the force of their creative power. Our civilisation has become a stagnant backwater, our religion a bigotry of externals, our spirituality a faint glimmer of light or a momentary wave of intoxication. So long as this state of things lasts, any permanent resurgence of India is impossible.

[With minor modifications in formatting--Editor]

All writings of The Mother and Sri Aurobindo are copyright of the Sri Aurobindo Ashram

Seer, poet and writer, unarguably one of the profoundest influencers of human thought and civilization in the last century, Sri Aurobindo is widely known and revered as a Maharishi and Mahayogi. He left his body in Pondicherry on December 5, 1950.

Continuing our series on Sanatan Dharma by Swami Krishnananda

Continuing our series on Sri Aurobindo and Integral Yoga

Continuing our explorations into the yogic secrets of the body with Alok Pandey